Lecture Series on Bauhaus Centenary and the 1st Memorial Anniversary of Da-Hong Wang| Theme 1: Rustic & Poetic—Architecture in Postwar Taiwan: Chinese Modern Architecture

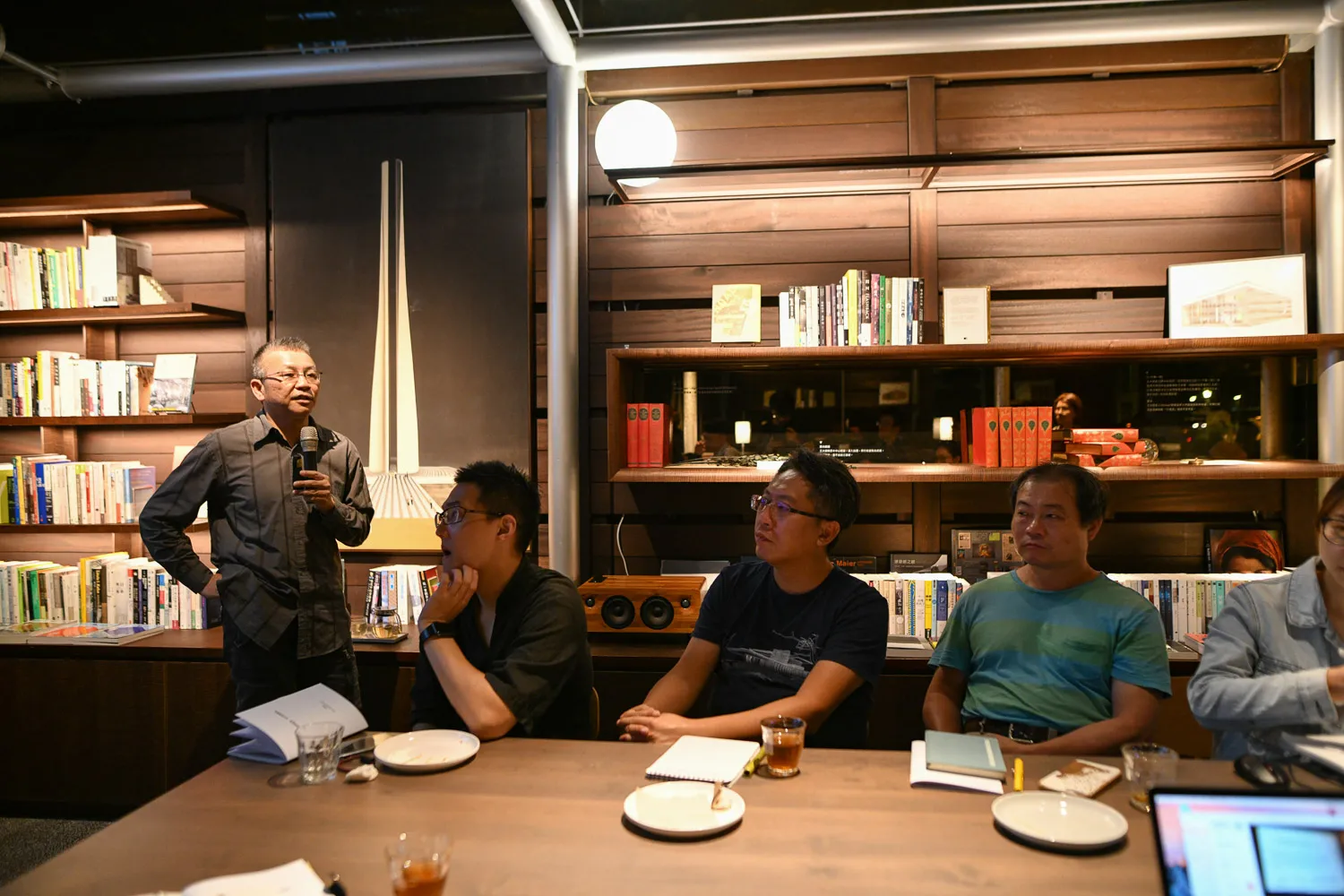

Speakers

Tseng-Yung Wang Founder of Bigger W Atelier

Chun-Hsiung Wang Director, Department of Architecture, Shih Chien University

Location

DH Café (No. 153, Section 3, Zhongshan North Road, Zhongshan District, Taipei City)

Fee

One lecture for $500, including special snacks (sandwiches, desserts, drinks), and 10% discount on event book purchases.

Introduction

Post-World War II architecture in Taiwan underwent profound transformations whose effects persist to this day. First, the historicism that characterized pre-war architecture was almost replaced overnight by modernist architecture. Second, the architectural profession, previously dominated by Japanese practitioners, faced a vacuum following the departure of Japanese nationals after the war. Following the Nationalist government's relocation to Taiwan, this void was largely filled by professionals who had migrated from mainland China. Furthermore, the professional certification system for architects, non-existent before the war, was implemented in Taiwan following the arrival of the Nationalist government. Finally, university-level architectural education, previously absent, emerged in Taiwan. This lecture series uses these historical shifts as its horizontal axis, while exploring four thematic verticals—Modernism, Christian architecture, Brutalism, and Chinese modern architecture—to initiate discussion on this often-overlooked chapter of architectural history. This session is “Theme 1: Rustic & Poetic—Architecture in Postwar Taiwan: Chinese Modern Architecture."

Event Review

In 1953, Wang Da-Hong and I. M. Pei simultaneously created two milestone works in Taiwan—Wang Da-Hong’s own residence on Jianguo South Road and I. M. Pei’s design for Tunghai University. Unbeknownst to each other’s project, both architects integrated traditional Chinese sloped roofs and red brick into the spatial and structural language of modernism, establishing themselves as pioneers of Chinese modern architecture in Taiwan.

At a time when the concept of a curtain wall was still unfamiliar in Taiwan, Wang Da-Hong masterfully accomplished one modernist building after another. Meanwhile, during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s across the strait, the Nationalist government in Taiwan sought to construct architecture rooted in Chinese nationalism to reinforce its claim to cultural legitimacy.

Beyond Wang Da-Hong and I. M. Pei, this era saw architects such as Chao-Kang Chang, Chi-Kuan Chen, Chang-Ming Chin, Tsu Hochen, and Er-Pan Kao contributing to a distinct Chinese modernist expression. Simultaneously, Kenzo Tange’s fusion of traditional Japanese timber structures with modernist techniques inspired Taiwanese architects to reinterpret tradition—not through replication or nostalgia, but through meaningful adaptation.

Decades after the development of Taiwan’s postwar architecture, it shows gradual evolution—transitioning from imitation (whether of modernist archetypes or palatial traditions) toward a renewed engagement with the land, the rhythms of daily life, and contemporary realities. Through collective effort, Taiwan continues to distill its own architectural ethos and cultural identity, as the journey is still ongoing.