Lecture Series on Bauhaus Centenary and the 1st Memorial Anniversary of Da-Hong Wang| Theme 2: Taiwan’s Architecture and Bauhaus— Seeking Tradition in Mies’s Austerity of Minimalism

Speakers

Ming-Song Shyu Architecture Historian, Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, Ming Chuan University

Location

DH Café (No. 153, Section 3, Zhongshan North Road, Zhongshan District, Taipei City)

Fee

One lecture for $500, including special snacks (sandwiches, desserts, drinks), and 10% discount on event book purchases.

Introduction

This year marks the centenary of the Bauhaus (1919-2019) and the first anniversary of Mr. Da-Hong Wang’s passing. Three Taiwanese architects profoundly influenced by the Bauhaus—Da-Hong Wang, Chi-Kuan Chen, and Chao-Kang Chang—each contributed in distinct ways to the development of post-war modern architecture in Taiwan. Though time has passed and the pioneers are gone, revisiting their legacy today still reveals astonishing cultural depth. On this centenary, it is essential to reflect on the vital cultural assets they bequeathed to us. This four-part lecture series marks the beginning of our profound reflection. This session is “Theme 2: Taiwan’s Architecture and Bauhaus— Seeking Tradition in Mies’s Austerity of Minimalism.”

Event Review

Wang Da-Hong spent his childhood in Suzhou, China, he was deeply immersed in traditional culture. At thirteen, his father was appointed a judge at the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague, marking the beginning of Wang’s seventeen-year journey of study and work across Europe and the United States. He lived in France, Switzerland, England, and America, enjoying both refined material comfort and intellectual life, until 1947 when he left Harvard, where his mentor Walter Gropius was teaching.

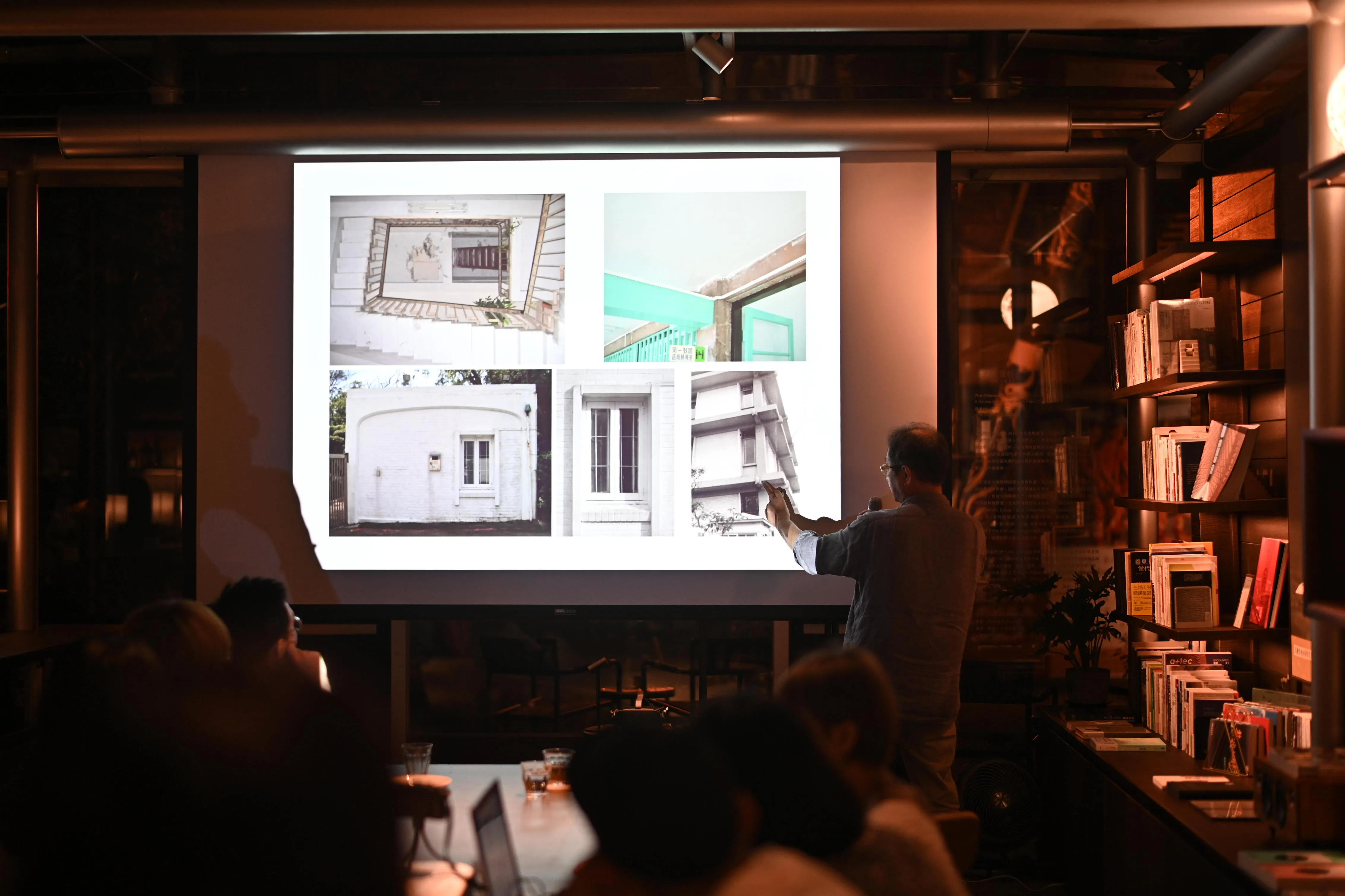

His solid grounding in both Eastern and Western culture, coupled with the influence of Bauhaus principles, naturally shaped his architectural style—merging minimalist modern spaces with the depth and sensibility of Eastern aesthetics. Wang described his design philosophy as “simplifying complexity”—integrating intricate ideas into pure forms and pushing them to their limits. This approach resonated with Mies van der Rohe’s “Less is more,” while also aligning with Daoist philosophy, forming a spectrum where tradition and modernity harmoniously converge.

As the civil war continued when he returned to China, in late 1952, Wang Da-Hong relocated to Taiwan with the Nationalist government, and remained there for the rest of his life. His personal trajectory, marked by rises and declines, mirrored the turmoils of his era. Political manipulation, along with capitalism’s inability to appreciate the subtlety of his introspective and refined aesthetic, led him in later years to focus on poetic pursuits like designing a lunar monument and engaging in literary creation.