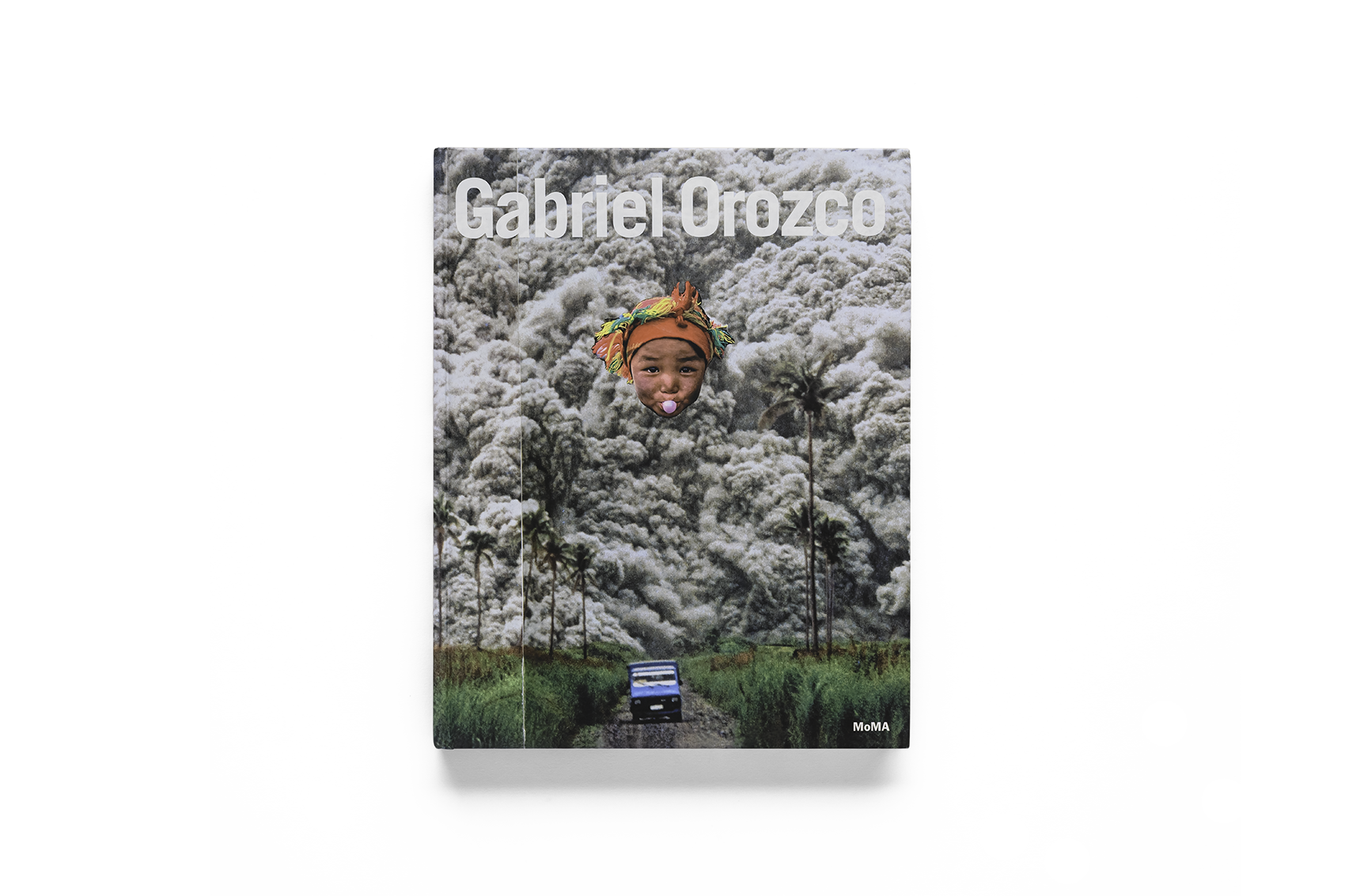

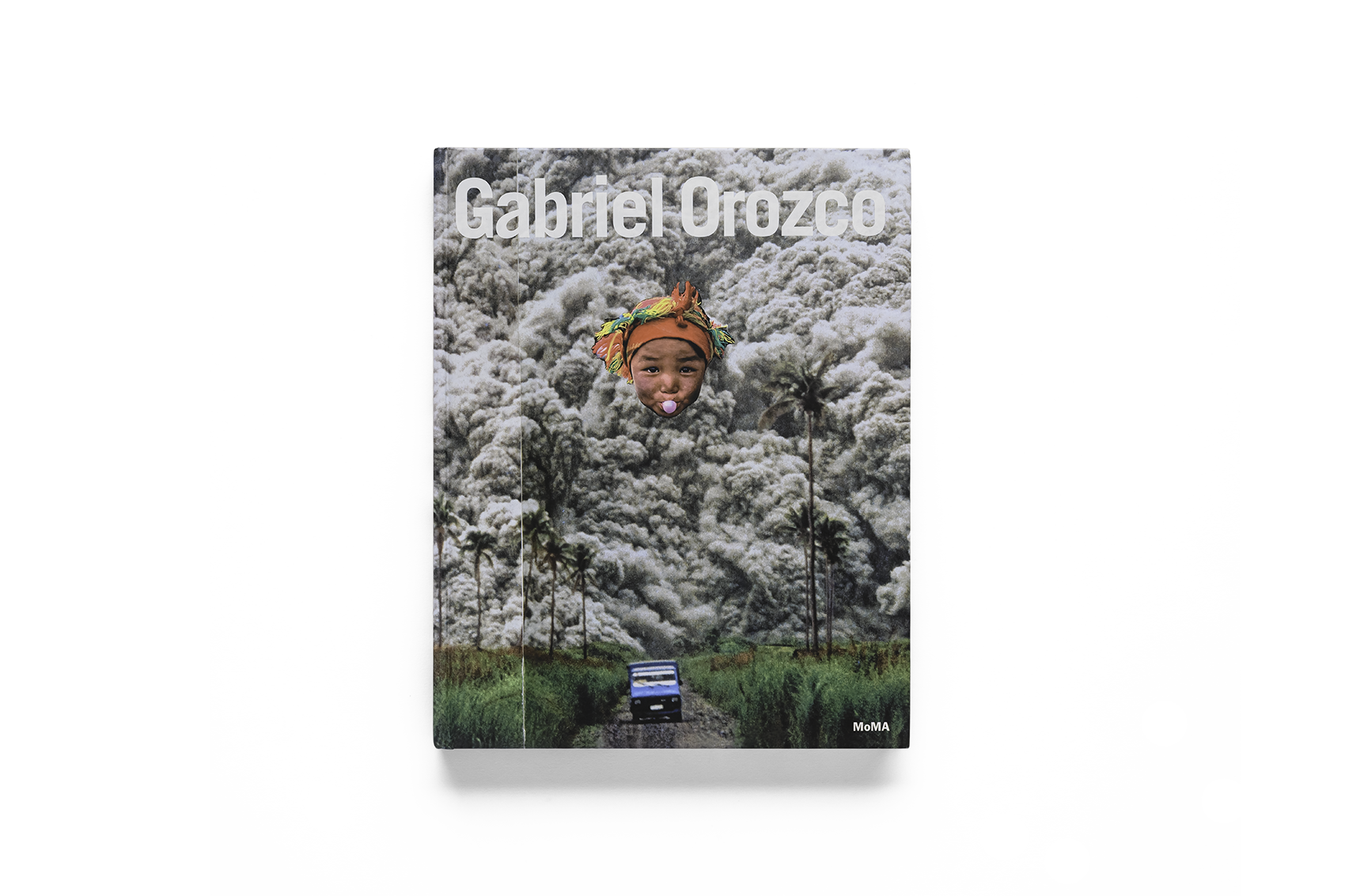

Museum of Modern Art, 2009

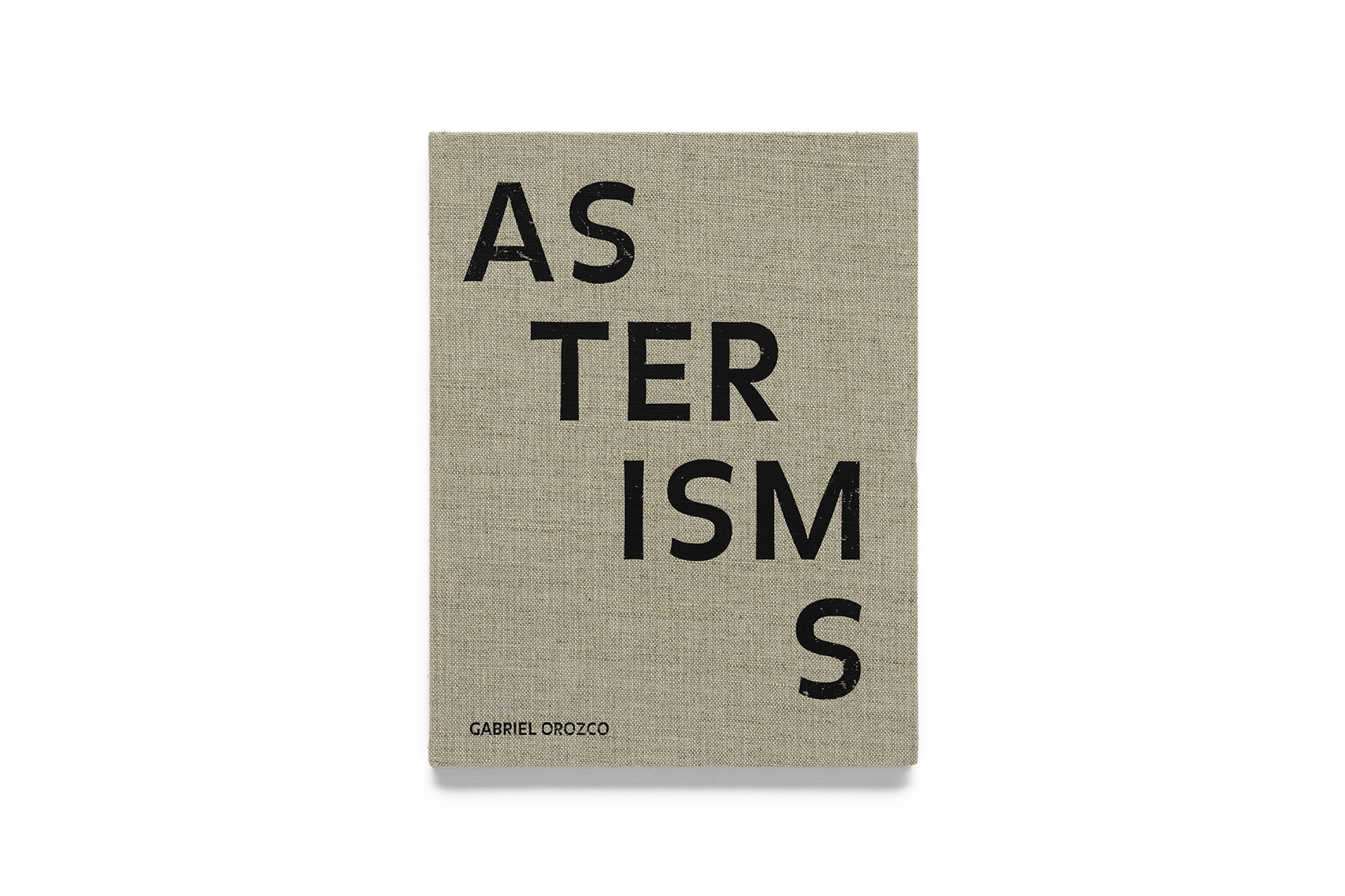

Gabriel Orozco

Museum of Modern Art, 2009

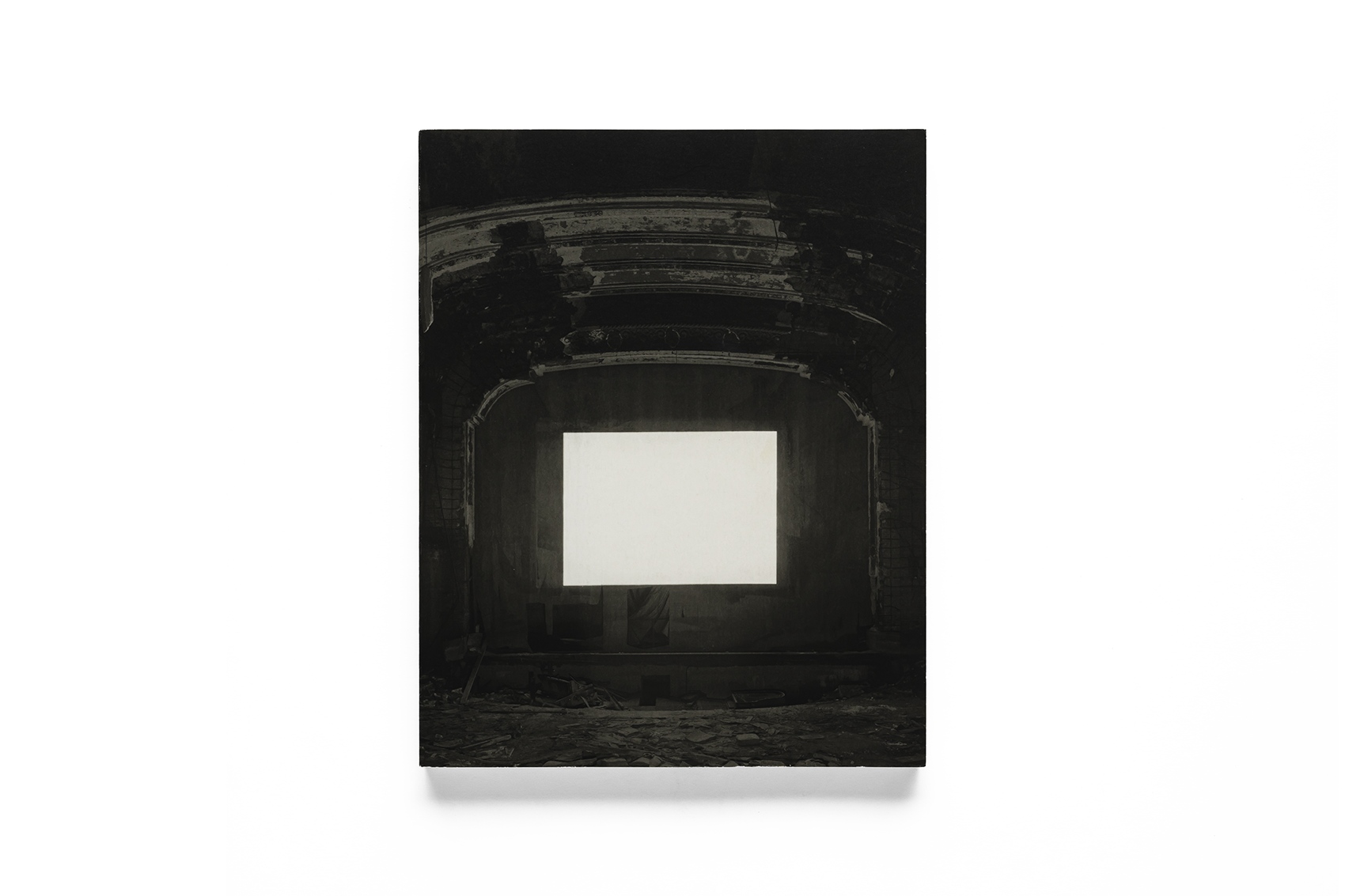

In 1993, Gabriel Orozco presented his first solo exhibition at New York’s MoMA, Projects 41: Gabriel Orozco. Among the works shown was Home Run, realized in collaboration with local residents who were asked to place oranges on their windowsills for the duration of the exhibition. In this way, the work extended beyond the walls of the museum—viewers could continue to encounter it even after leaving the galleries—breaking down the boundaries of the “space of viewing.” The exhibition as a whole reflected Orozco’s enduring interest in immediacy, objects, and their relationship to the surrounding environment. Sixteen years later, in 2009, Orozco returned to MoMA with a major retrospective, presenting sculptures, installations, photographs, paintings, and drawings from the 1990s through more recent years. The exhibition subsequently traveled to Kunstmuseum Basel, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and Tate Modern in London.

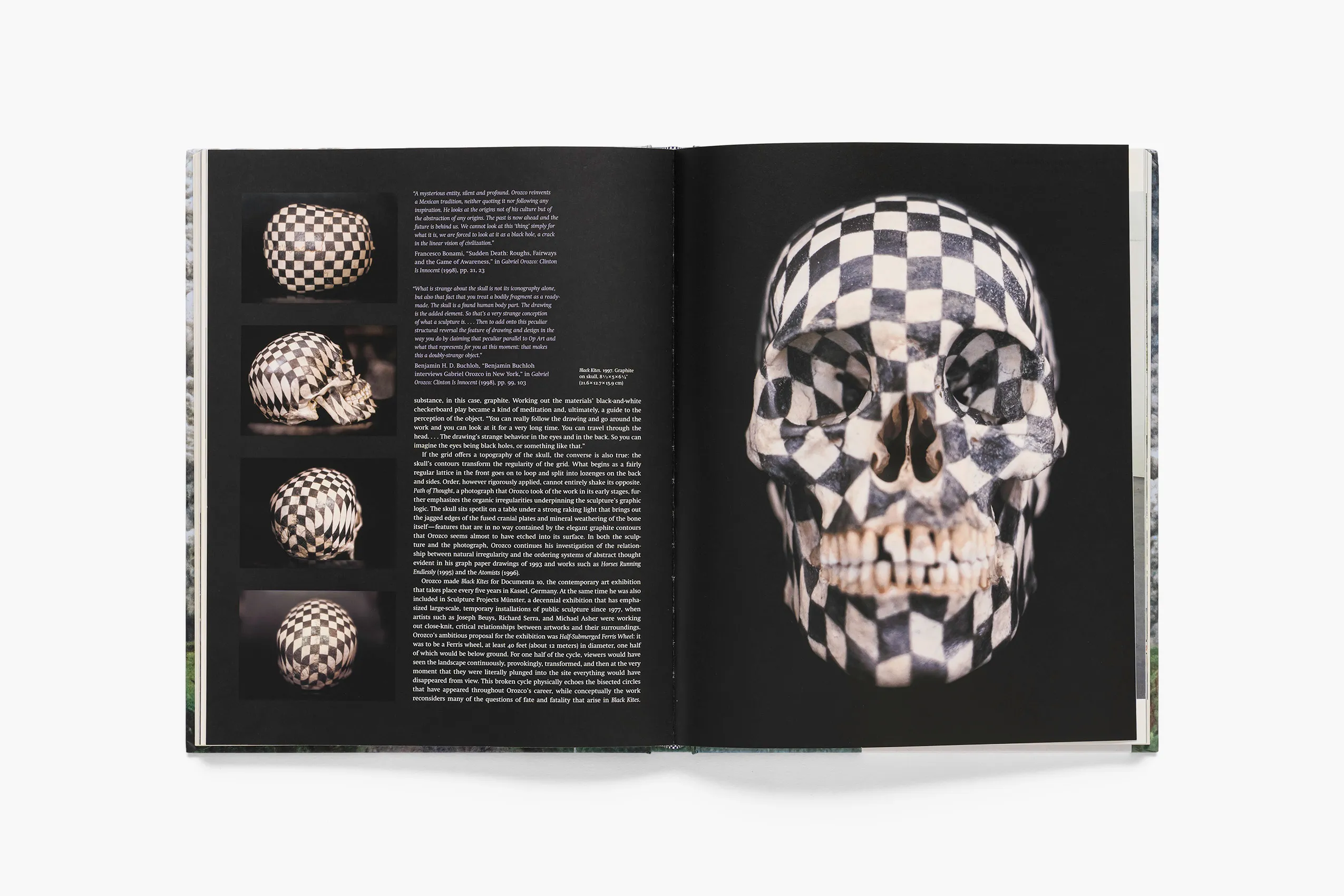

Orozco’s sculptures are frequently composed of found objects that capture his attention, reframing the familiar in unexpected ways. One of his earliest works, Recaptured Nature, was created from a discarded truck tire inner tube transformed into a movable sphere. The piece reflects both his exploration of diverse materials and his sustained investigation into circular forms. In Empty Shoe Box, Orozco placed a single empty shoebox on the floor, using the object to redirect viewers’ attention toward their surroundings and establish a dialogue between audience and space. This work was also included in the 1993 Venice Biennale. During a period of convalescence from a lung illness, Orozco devoted several months to the creation of Black Kites, a skull intricately covered in a graphite grid. The work underscores the theme of life’s transience, a subject made all the more poignant by the artist’s own circumstances at the time. A print version of this work is currently on view at Winsing Art Place.

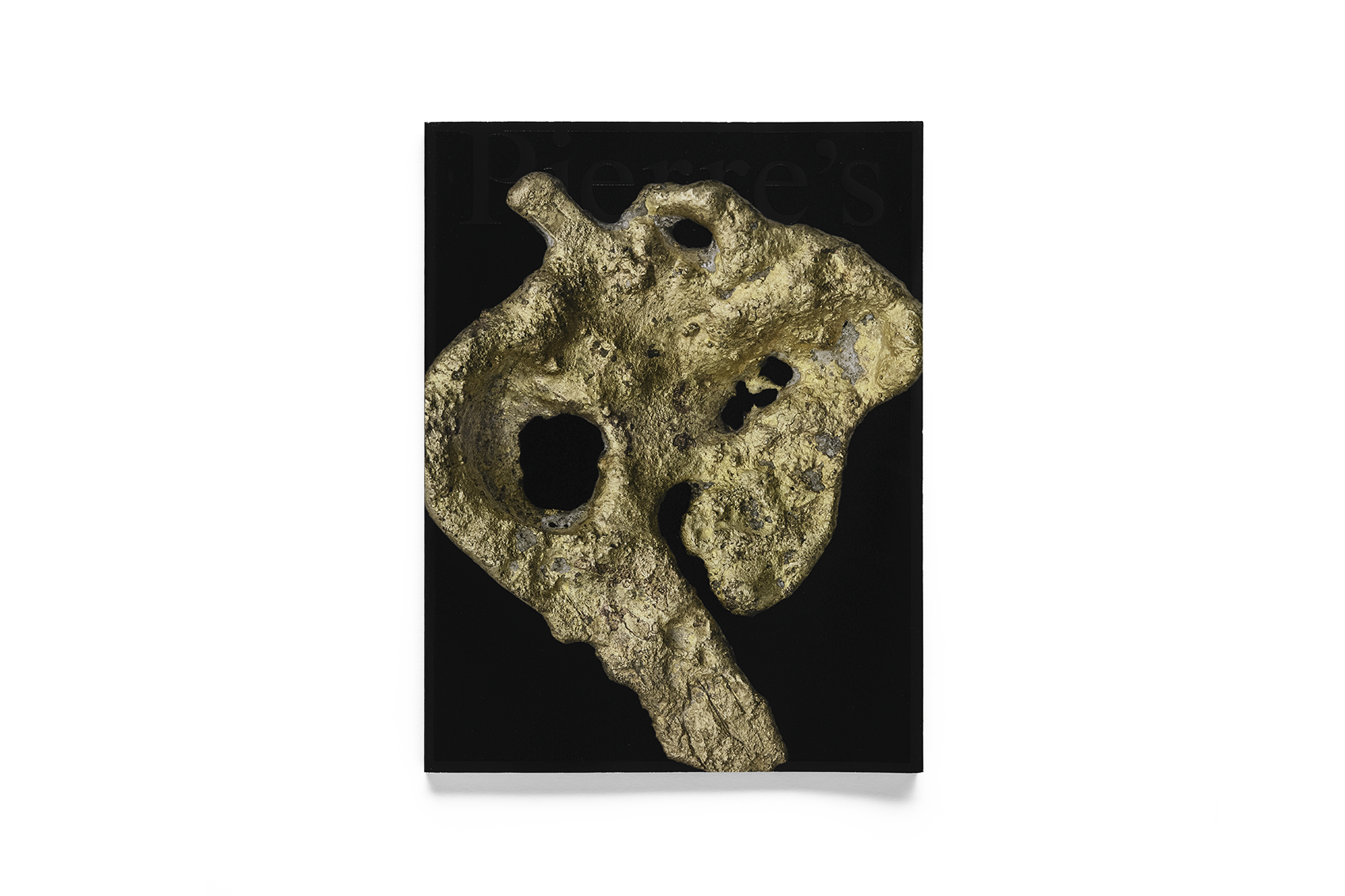

Black Kites was not Orozco’s first engagement with bones. Another monumental installation, Mobile Matrix, stood at the entrance of his MoMA retrospective and became one of its central works. For this piece, Orozco and his team recovered the skeletal remains of a whale from Isla Arena in northwestern Mexico. After extensive cleaning and restoration, the team spent six weeks inscribing the bones with graphite using 6,000 pencils, creating a vast drawing that reflects the artist’s investigations into anatomy, geometry, and scale.

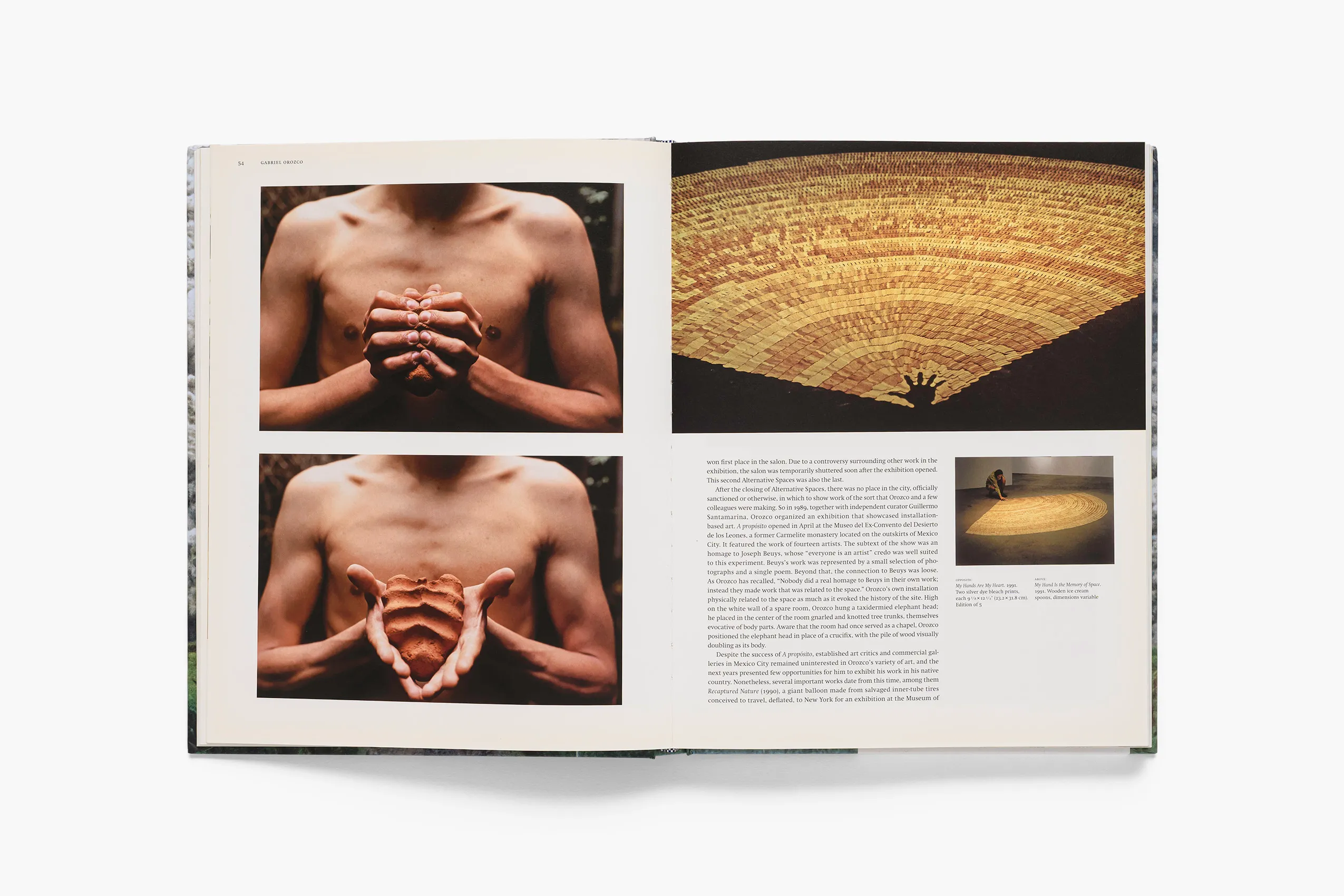

Orozco’s nomadic way of life deeply informs his practice. Beyond sculpture and painting, photography has long been one of the key mediums through which he engages with his everyday experience. As he once noted: “I think photography must respect reality, to enjoy those contradictory moments between life and death, between sleep and wakefulness. I simply use the camera as the best way to capture or convey those moments. It becomes a tool—just like painting—that has always been a constant in my work.”